Uncovering The Chicano Mind

In the early 1970s, Pasadena City College student Guillermo Martinez painted The Chicano Mind, a monumental mural that captured both the energy of the Chicano Rights Movement and the revolutionary spirit on campus. Created under the mentorship of artist Ben Sakoguchi and shaped by the new Chicano Studies courses that emerged from student and faculty activism, the work reflects Mexican muralist traditions while chronicling the struggles and contributions of Mexican and Mexican American people. More than an artwork, The Chicano Mind embodies the political debates, cultural pride, and educational transformation that defined PCC in that era.

In Spring 2025, students in Dr. Anna Kryczka's Humanities through the Arts course embarked on a semester-long project to recover the painting's legacy. Prior to undertaking this project, this monumental work of art had no plaque and no digital footprint. In order to protect the work from future censorship or destruction, the class conducted their own individual visual analyses as well as collaborating on writing essays to put the work into its artistic, cultural, institutional, and historical context. The goal of these efforts is not only to bring attention to The Chicano Mind's meaning for the current climate but also to start a student-driven conversation about the role of public art at PCC in the future.

Learn About "The Chicano Mind"

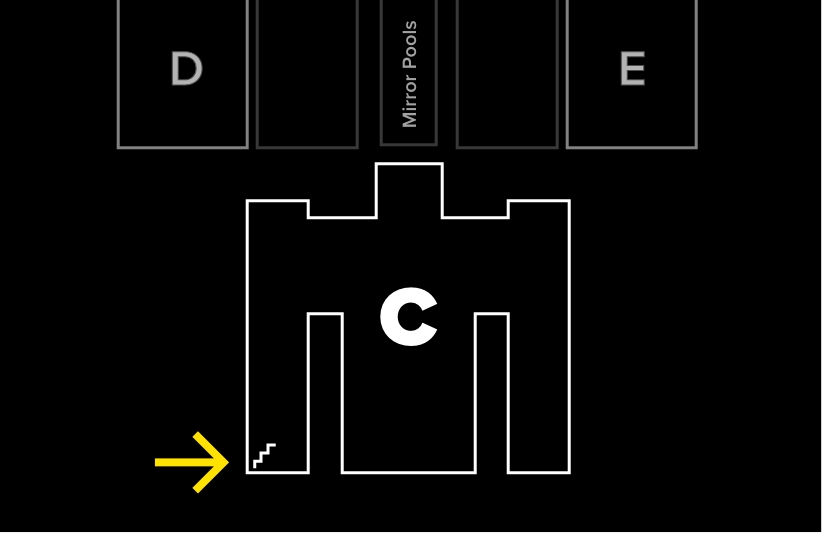

Visit the Mural

Located in the southwest corner of the C Building, between the 2nd and 3rd floors. Directions

Contextualizing "The Chicano Mind"

By Anna Kryczka

Resisting longstanding patterns of segregation and dehumanization and the legislative progress of the civil rights movement being met with intensive local inertia, the people of Los Angeles County launched numerous revolutionary social movements throughout the 1960s and 70s. You can learn about the Chicano Rights Movement in particular from this student-written overview. The late 1960s and early 70s at PCC were a period of intense political discourse resulting in major changes in academic course offerings as a result of intensive student and faculty organizing. In the April 30, 1969 edition of the Courier, journalists reported on the establishment new coursework and area offices:

Courses now offered include Afro-American writers, history of Sub-Saharan Africa, history of the Afro- American to 1865, and from 1865, sociology of the AfroAmerican, Swahili, ethnic dance, African art, Afro- American Music; as well as Mexican anthropology, Mexican-American history, Mexican philosophy, and psychological characteristics of the Mexican American.

These course offerings are remarkable and reflect the expansive thinking around the role of community college education. Numerous letters to the editor published in the Courier make clear that the campus climate was polarized and not united in support of the growth in ethnic/area studies. A wide range of attitudes found expression, from a dismissive letter from an Anglo student calling for the creation of “Martian Studies” to a letter from a self-identified Spanish American student who described what he saw as futility of ethnic studies in the face of the necessity to assimilate to cope with what he describes as a WASP dominated culture to an anonymous letter that questions how progress towards eradicating racism can be made with a truthful form of education that reveals rather than obscures. These debates persisted throughout the early 1970s as these statements of support from the October 15, 1976, editorial page Courier reflect:

Asian Affairs Office, Pan-Afrikan Affairs Office, and MeCHA office are critical for combating bigoted attitudes. - Jim Hight student

“This ‘special treatment’ is necessary because of the barriers that white society has put in the way of oppressed minority students. At PCC, these programs are pitifully small. There is no separate Black or Chicano studies or women’s studies department. The few gains that minority students have made must be preserved and expanded, not taken away. The new offices in the campus center are, therefore, not an extravagance but a small step in the right direction. -Joanne Tortorici & Peter Link, PCC Young Socialist Alliance

If more blacks attended Chicano Studies and more caucasians attended Afro American Sociology, perhaps individuals would become more accepting of the needs of their fellow men and thus increase their knowledge of and pride in the heritage. -Vince Mercade

Reporting in the Courier throughout the 1970s revealed the fight for affirmative action in hiring was led by MeCHA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán), UMAS (United Mexican American Students), and La Raza Faculty Association. Professor of history and Asian American Studies Susie Ling asserts that “except for SFCC, I believe PCC is the only California community college that has continuously taught ethnic studies since the 1960s.” The tireless advocacy and activism of faculty, students, and staff have made this possible. Superintendent President Armen Sarafian facilitated and supported this revolutionary transformation in course offerings impacting generations of students.

Artist Guillermo Martinez was a student in several Chicano Studies classes during his time at PCC and stated that these classes alongside his training with Professor and renowned artist Ben Sakoguchi and exposure to the work of Mexican artists informed his massive composition hanging in PCC’s C Building.

Martinez reflected on the project in a 1983 Courier article:

The Administration asked the Art Department to get together a group of students to do a mural. At that time, Ben Sakoguchi was my teacher, and he said I could do the job totally by myself.

I had done one mural painting before at Annendale Elementary School a few months before. At that time I was taking 18 units. I was working towards my AA. I started at PCC when I was a junior in high school as a special student. I studied mostly with Sakoguchi and Doug Bond. I also studied at the Pasadena Art Museum, later bought by Norton Simon. Michael Mahan was my instructor there.

You start with a scale drawing, then comes the construction…buying materials, the stretcher bars, then I prepared it with gesso.

At that time, the cafeteria was under construction and before they built new offices, I was able to use that space. There were some people waiting for me to get done. They could move in, install phones. Etc. So I didn’t delay the project any longer than needed. From the time I started putting paint on it, it took two months. Actually I do recall asking for extended time on the project because of my studies. The administration was very sensitive and liked the way the project was coming along. I was working under Dick Cassidy, the art director then. He was like the middleman on the project - he dealt with me and with the administration.

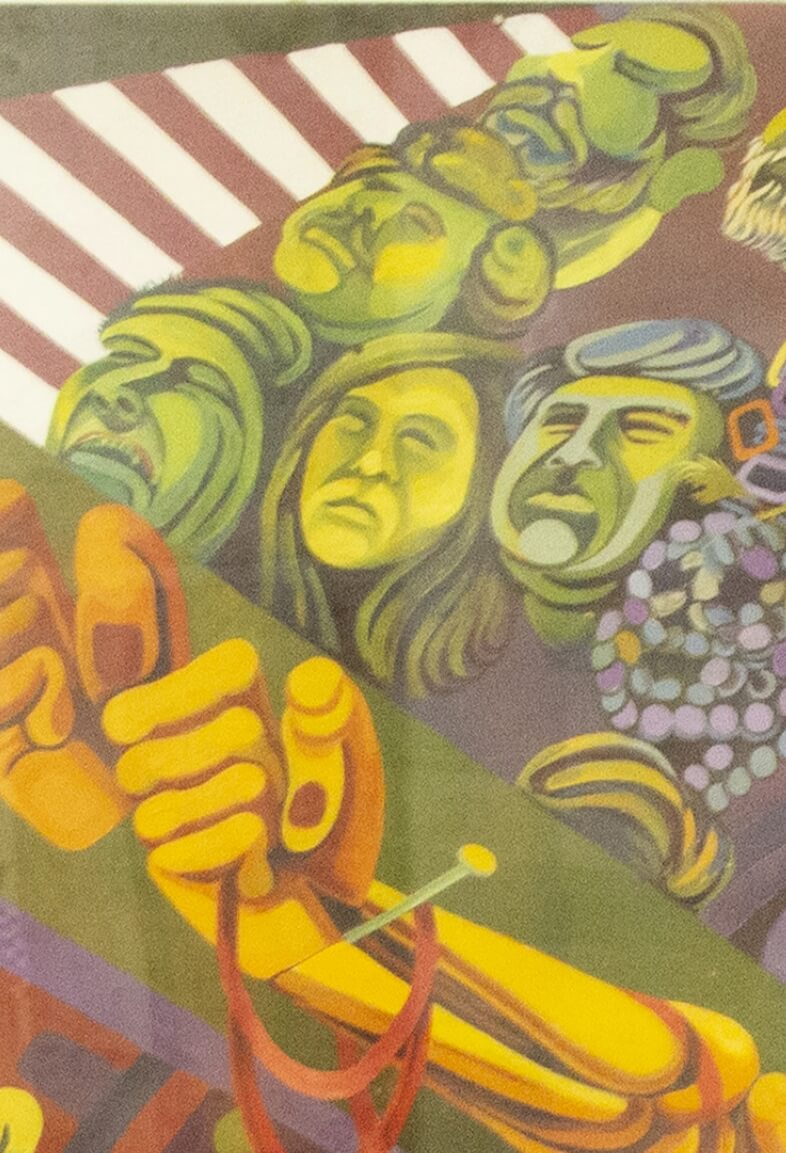

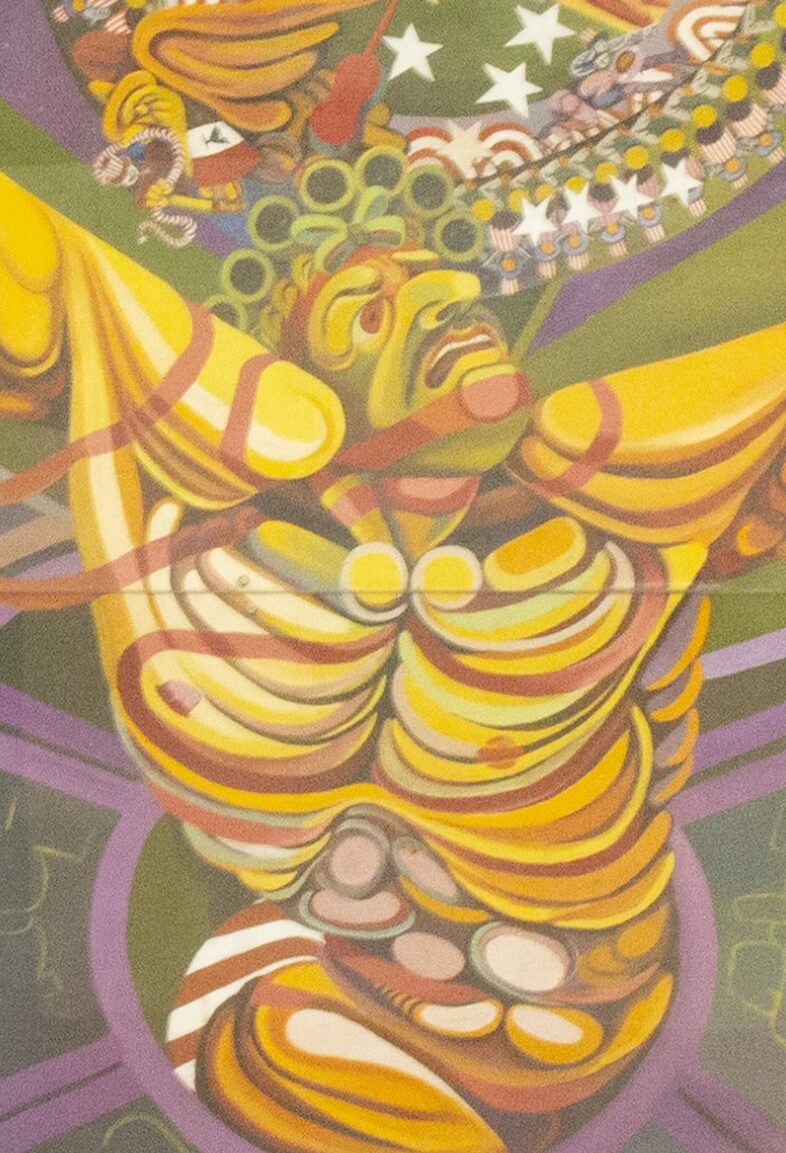

There’s a central figure in the oil painting representing a race of people, “la raza,” and he is projecting images of himself.

That painting had a lot of the Mexican muralist’s influence. You see a lot violence and energy depicted in their works. It came about from my study of their particular style. At the time I was taking several Chicano studies classes which helped me decide into which direction the painting would go. So below the center figure, it depicts those who participated in Mexico’s history from the ancient times to the present. Above the center figure are Mexican Americans who participated in our history in the southwestern part of the United States.

This spontaneous act of creating a monumental work of public art is remarkable. The autonomy and trust granted to both students and faculty by the administration is notable as well. Monumental works of public art, both commissioned and spontaneous, have been of LA’s built environment and functioned as forms of political speech and cultural self-representation. You can learn more about this long tradition in this student-written overview. Reflecting on Martinez in a 1996 Courier article, Sakoguchi stated “I’ve been teaching for 33 years and that guy stuck out. He has something in him, he was an outstanding artist.” Read current PCC student analyses of Martinez’s work here. The artists and publications and institutions that emerged from the late 1960s and 1970s illuminated a cultural revolution, you can learn more about the art and work of this time in this student-written overview.

The work was vandalized in the 1990s and was later restored by Sakoguchi in 1993. Martinez asserted in a 1993 Courier that he felt his work was targeted because “certain people might not like it because it was a Chicano mural.” The late 1980s and early 1990s in California were deeply shaped by xenophobic policy stances on undocumented people, police brutality, the unrest in response to the acquittal of the law enforcement officers who beat Rodney King and lenient conviction of the shopkeeper who murdered Latasha Harlins, and the creation of many local laws across the San Gabriel Valley requiring English language signage.

1994’s Proposition 187, also known as the Save Our State initiative, had its roots in the San Gabriel Valley, having been launched by a state assembly member representing Monrovia. The proposition sought to exclude undocumented immigrants from access to public services, including the exclusion of children from public schools. The proposition crafted a typical racist scapegoating narrative, blaming undocumented people for the state’s budget crisis and voters approved the ballot measure in a statewide vote.

Gary Leonard, Proposition 187 Protest Downtown LA, 1994. (Calisphere)

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), an organization founded in 1968 in response to the attempted repression of the Chicano Rights Movement, led the legal case to challenge the constitutionality of the proposition. Massive protests, and school walk outs in opposition to the provisions of the proposition occurred across Los Angeles County. The exclusionary provisions of the proposition failed in court and the effort to exclude undocumented people from the “public” found no legal basis at that time. The false and racist narrative presented by prop 187 persists as a tool for political organizing in the 21st century as we see continued local and national efforts to dehumanize and expel undocumented people.

Martinez returned to PCC in 1996 to take more art classes, but kept a low profile, according to the Courier. The Chicano Mind stands as a monument to the politics and environment of the campus and community in the early 1970s. Its neglect since the 1990s is troubling, it has been my honor to work alongside my students to recover this work and the contexts to which it connects. The LA artists and activists of the late 1960s and 70s set down political and institutional roots and legacies that young artists and organizers continue to build on and expand. You can read more about contemporary Chicanx artists carrying forward the legacies of the movement in this student-written overview. For Martinez, seeing his work 30 years later made him reflect on what the Mexican and Chicano people have gone through and “to realize our struggles aren’t over.”

Understanding the Chicano Rights Movement

By Jasmin Abrego Menendez, Benjamine Duran, Rachell Luis, Isabella Smith

The expansion of the American Empire during the 19th century led to the oppression of the Mexican community—affecting the structure of social class and educational/learning development within. After facing defeat by the United States in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was consequently signed which offered rights concerning education, religion, property, etc. However, these rights were limited to Mexicans who still inhabited the newly obtained territories of the United States. This treaty was not upheld by the U.S. government, leading to the colonization and oppression of the Mexican peoples affecting their culture, properties, and ways of living.

From this, we can understand that the racism towards Mexican people is not something new. It is something deeply rooted into the history of the United States, and something which has, unfortunately, only proliferated itself more overtime. Now, we can understand the Mexican people getting colonized twice, once by the Spanish, and another time by the United States. Not only was the colonization physical, but for those Mexicans left in U.S. territory; it was cultural. Beginning with the conquest of the west by the U.S. we can observe efforts to “Americanize,” seeing the American way as superior and the only way, thus in addition to imperialization there was also a cultural imperialization that was occurring, where peoples other than Anglos were seen as lesser and inferior. The Chicano Movement, which began in the 1960s and was inspired by the broader Civil Rights Movement, marked a turning point where Chicano people, after decades of racism and oppression, collectively decided to fight for their equality.

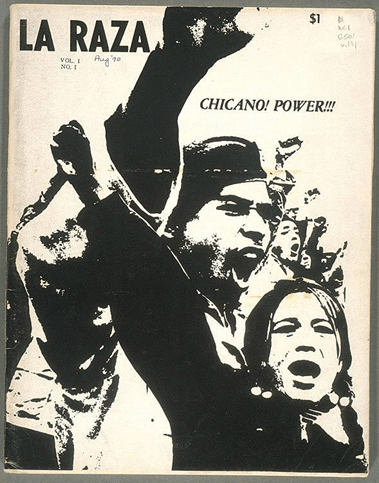

Cover of the Publication La Raza (JSTOR)

Through an in depth exploration of our assigned readings and screenings, we have developed a comprehensive understanding of the Chicano Movement as a powerful intersection of civil rights activism, cultural affirmation, and systemic resistance. These materials including The Chicano Movement: Mexican American History and the Struggle for Equality by Carlos Muñoz, From Military Industrial Complex to Urban Industrial Complex by Raúl Villa, If You Build It, They Will Move by Gilbert Estrada, The Dialectics of Repression by Edward Escobar, and the documentaries La Raza and 1968 LA School Walkouts reveal how Mexican American communities confronted racial discrimination, police violence, educational inequality, and displacement. Together, these works deepen our understanding of how activism was shaped not only by identity and pride but by the urgent need to resist structural oppression on multiple fronts.

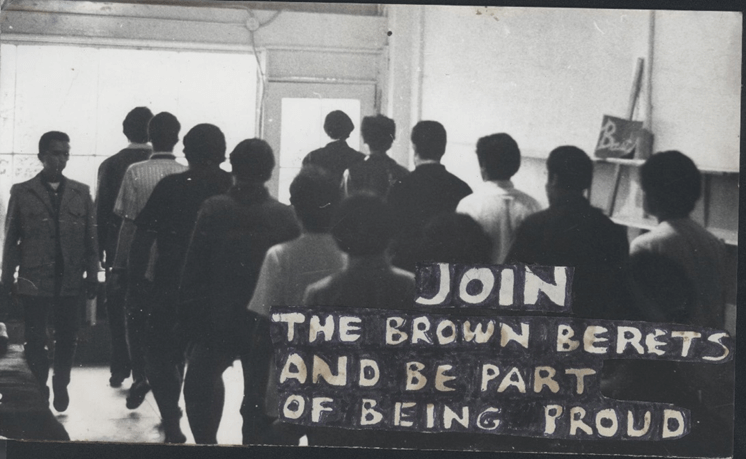

First, Carlos Muñoz’s foundational work offers a historical overview of the Chicano Movement, tracing its origins through grassroots organizing and the growing political consciousness of Mexican Americans during the 1960s and 70s. Muñoz focuses on the importance of cultural pride, identity formation, and student led activism in shaping the movement’s ideology. His coverage of the 1968 student walkouts and the rise of youth organizations such as the Brown Berets shows how activism was often led by young people demanding more equitable treatment and representation. Importantly, Muñoz blends historical narrative with personal experience, providing both scholarly analysis and emotional insight. His work lays the groundwork for understanding the broader goals of the movement social justice, self-determination, and systemic reform.

Flyer recruiting members to the Brown Berets (Calisphere)

While Muñoz addresses ideological and political motivations, Raúl Villa’s From Military Industrial Complex to Urban Industrial Complex focuses on the physical and spatial dimensions of oppression, especially in postwar Los Angeles. Villa argues that urban development policies, including freeway construction and gentrification, disproportionately targeted Chicano communities for displacement. Rather than being neutral, city planning served the interests of elites while undermining working-class neighborhoods. Villa’s work was particularly eye-opening in how it connects urban infrastructure to racial inequality. His analysis reframed our understanding of displacement not as a byproduct of progress, but as a deliberate act of state power aimed at controlling and marginalizing racialized populations. By highlighting art, murals, writing, and protests, Villa emphasizes how Chicanos used creative expression to resist erasure and to reclaim their identity within urban spaces. This perspective positions the Chicano Movement not only as a cultural struggle but also as a fight for spatial justice and the right to remain rooted in one’s community.

Gilbert Estrada’s If You Build It, They Will Move complements Villa’s analysis by offering a detailed case study of freeway development in East Los Angeles between 1944 and 1972. Estrada uses historical records and policy analysis to demonstrate how the state used eminent domain and urban renewal language to justify the removal of Mexican American families from their homes. His examination of the Chavez Ravine evictions was especially powerful, showing how even public housing projects became tools of racialized displacement. This reading illuminated how systemic racism was embedded in policy and infrastructure, not just in interpersonal prejudice. “East Los Angeles became a testing ground for freeway engineers—and Mexican Americans paid the price.” Estrada’s work helped us understand the deep connection between displacement and the rise of Chicano political activism, particularly how these injustices led many to mobilize in defense of land, housing, and cultural survival.

Residents being forcibly removed from their homes in Chavez Ravine, 1959 (Calisphere)

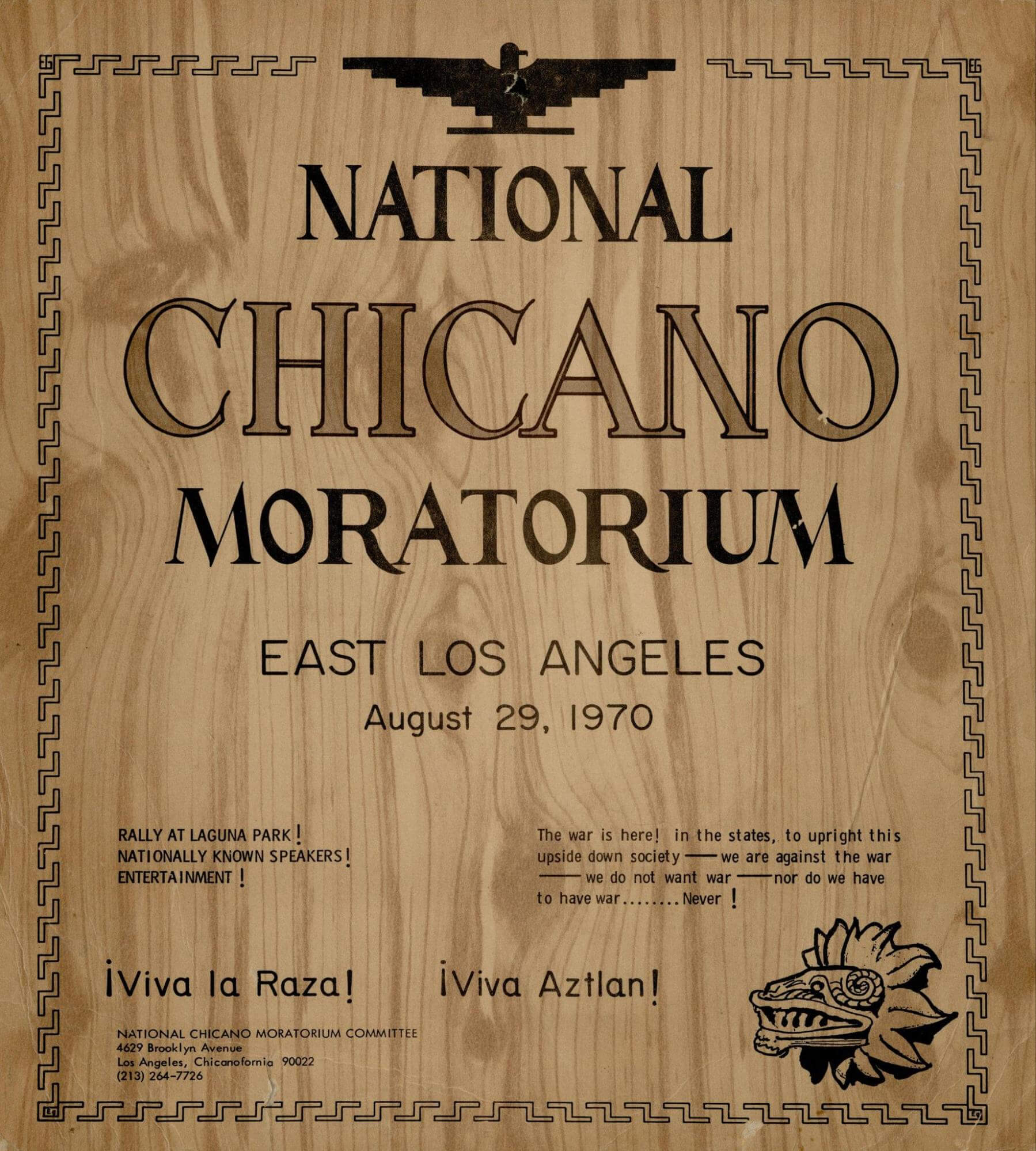

Edward Escobar’s The Dialectics of Repression shifted the focus from urban policy to policing and the criminalization of dissent. Escobar provides a critical examination of the Los Angeles Police Department’s efforts to monitor, infiltrate, and repress Chicano activists during the height of the movement, particularly between 1968 and 1971. His analysis of the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, an anti Vietnam War protest that ended in deadly police violence was a turning point in our understanding of how the state actively worked to suppress movements advocating for racial justice. Escobar introduces the idea that repression can strengthen movements by exposing the very injustices they seek to combat. We learned that while law enforcement aimed to silence Chicano leaders, the state’s heavy handed response often radicalized activists and attracted wider support. “Chicano activists were labeled radicals not because of violence, but because they demanded systemic change.”This dynamic of resistance and repression underscores the risks Chicano activists took and highlights the movement’s courage and resilience.

Flyer for the Chicano Moratrium (JSTOR)

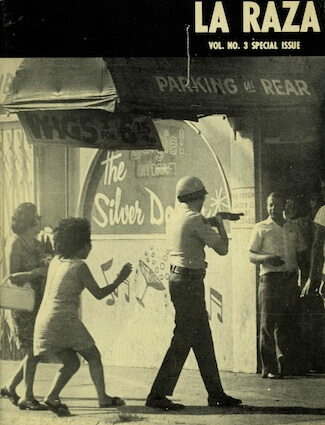

The La Raza documentary provided a visual and narrative complement to the readings, focusing on the power of independent journalism in shaping the Chicano Movement. The film chronicles the development of La Raza newspaper and media collective, which documented police brutality, protests, and daily life in Chicano communities. What stood out most was how the media became a strategic tool for reclaiming agency over representation. In an era when mainstream outlets ignored or distorted Chicano issues, La Raza offered an authentic, community driven counter narrative. This documentary emphasized that activism wasn’t limited to marches or speeches; it also happened behind the lens, in newsrooms, and in storytelling. It showed us that cultural production was a central pillar of the movement, used to both inform and empower.

Cover of La Raza reporting on the assassination of Ruben Salazar (Calisphere)

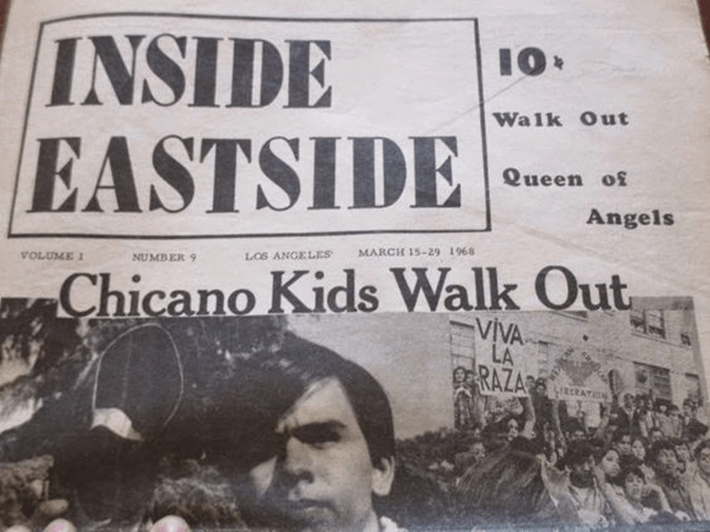

Finally, the 1968 LA School Walkouts documentary offered a vivid portrayal of student-led resistance and the importance of education in the broader fight for equality. Through interviews with participants and archival footage, the film highlighted how thousands of Chicano students walked out of class to protest racist teachers, Eurocentric curriculum, overcrowded classrooms, and limited college access. Sal Castro, a Mexican American teacher and mentor, played a key role in encouraging youth to speak out and demand systemic reform. This documentary underscored that youth activism was not only reactive but visionary students articulated a clear and ambitious agenda for educational justice.

Cover of Inside Outside, a Chicano newspaper, detailing school walk outs. (JSTOR)

In synthesizing these six sources, we came to understand the Chicano Movement as a multidimensional struggle rooted in lived experience and collective resistance. It was not merely a civil rights movement, but a radical reimagining of what justice, identity, and community could look like for Mexican Americans. Each reading and screening contributed a unique lens political, spatial, cultural, or generational that, when combined, formed a comprehensive portrait of a movement fighting against deeply embedded systems of oppression. Overall, we learned that the Chicano Movement’s legacy lies not only in its victories but in its vision of a demand for justice that extended across media, institutions, and generations.

Defining & Understanding the Role of the Arts in the Chicano Rights Movement

By Frida Ibarra, Michelle Mejia, Lina Raoub, Hannah Peterson

When examining any piece of Chicano art one must look to its predecessors, its community, for any form of Chicano art is not made as an individual exempt from its surrounding history. In particular, the artists emerging during and after the emergence of Chicano Arts movement built a practice embedded in the world of social protest, not the art world. As stated in Looking for Alternative; Notes on Chicano art, community has always been a centerpiece in the movement. “As an art form it posits a social and cultural experience within an aesthetic system developed from layers of tradition, imagination, and struggle. Social engagement forms the meaning of this work.”(Brookman, 1).

Philip Brookman shows how Chicanos have been struggling with their situation for long, and they have used their creativity to accomplish their goals by using their traditions, imagination, struggles, culture and social engagement; thus, adding a meaning into their work. Chicano artists redefined their traditions and produced a new world view that presented alternative mechanisms for affirming their history and experience. They created new ideas to serve education, politics, and aesthetic goals for their communities. They considered themselves “Mestizos” meaning mixed. War and empire, both past and present, played an important role in colonial and post-colonial identity formation. Chicano art played a role of protest because in part it developed from a political movement and another part because it stems from a desire to document histories and realities that have excluded them from the mainstream or society. In addition to this, Chicanos realized that racism was as prevalent in the military as on the home front where the Vietnam war helped speed up the Chicano movement. This event has created a collaboration among artists from different cultures to become a predominant theme. The arts became a tool of critique and visibility, connecting the politics of the present to the past in an effort to also imagine a more just future.

In the article The Iconography of Chicano Self-Determination: Race, Ethnicity, and Class by Shifra M. Goldman the subject of race and ethnicity in regards to Chicano culture and how these two aspects of one’s identity relates to class are explored. The article begins by explaining how Chicano art is reflective of the oppression, class wars, and erasure perpetuated onto the culture by Anglos. This form of art celebrates the complexities of Chicano culture when it comes to race, ethnicity and class in a time where Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were heavily oppressed. Mexican people were not only discriminated against, but the existence of their culture was in danger as well. To celebrate and hold onto their culture that was under siege, Chicanos created art that celebrated their non-European lineage. This was swept under the rug due to Mexican people being under the heavy pressure of the Anglos to refer to themselves as “Spaniards.”

“Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl”, by David Botello, Juan Gonzalez, and Robert Arenivar in 1975, East Los Angeles

The Indigenous side of the Mexican people was under attack, the Europeans were successful at almost entirely annihilating Native Americans in the United States and they wanted to do the same down South. The Mexican people were rightfully resentful, and though oppression was extremely active, many artists attempted to keep their Indigenous roots alive through their artwork. The Mexican community in North America was forced into the working class, by seizing their land and proletarianizing them, they were pushed down to the lower classes of society. Chicano culture remains strong, for decades this community has celebrated their heritage and their culture through art and other forms of expression. This form of art celebrates the complexities of Chicano culture when it comes to race, ethnicity and class in a time where Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were heavily oppressed. Through cultural resistance, and celebration through art and expression, it maintained a strong presence. Chicanos and Mexican-Americans remained true to themselves in any way they could, in front of everybody, with their heads held high and they continue to do so. These values manifest in a visual iconography familiar to most living in Los Angeles in which pre-colonial Aztec, Maya, and Olmec imagery intermingles with Mexican Revolutionaries like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata giving way to later heroic representations of labor organizers Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta or journalist Ruben Salazar. This shared iconography is on display in The Chicano Mind.

The excerpt, “Con Safos C/S: A Contingency Factor,” written by Mel Casas, connects the political and creative power of artists during the Chicano Movement. Artists similar to Guillermo Martinez have used their artistic skills to defy “cultural genocide” (Casas) and “resuscitate and regenerate a wounded culture” (Casas) amidst the fight for civil rights. The idea that cultures must conform to an arbitrary quota of assimilation has become the apex of racism and discrimination, the driving force for the destruction of communities. Casa uses the title “Con Safo” as a descriptor for themselves and other artists united in the preservation of the Chicano voice; direct translations are “with safety” or “with respect.” C/S is commonly used as a symbol of unity and alliance among Chicanos and Latinos. Casas illuminates the mindset of a Con Safo; to be a C/S is to liberate the silenced through art by creating murals and portraits that immortalize the images of Chicanos. Guillermo Martinez would be considered a Con Safo based on his contributions to the artistic fight against oppression towards Chicanos. His mural amplifies the stories and history of Chicanos, imploring the public eye to take a moment to understand the impact of Chicanos.

Sun Bathers of Estrada Courts, Gil Hernandez, 1973.

As for “ Notes on an Aesthetic Alternative” by Chicano artist Carlos Almaraz, it discusses that art is not only inspirational and educational, but it forms a sort of aggression and hostility towards present bourgeois standards. For Chicanos, art must be more than just a matter of cultural identity. It must be confrontational, revolutionary, destructive. They believed that art should be part of the movement and that it can be simple and cheap yet make it alive, meaningful and informative. Almarez underscores the way that narratives of so-called modern art are themselves colonial in structure.They believed that art should be made for mankind to create some disturbance or maybe a small revolution that shows their struggles and brings in humanity. Through art, people can communicate identity and beliefs, preserve traditions and knowledge, foster connection and community and finally challenge existing norms and perspectives. As it is shown on the mural art at PCC, the image reflects what the Chicanos have faced when you look at faces being sad, seeing only heads which might suggest death of innocent people, the torture of someone crucified and how the people wanted to revenge by adding the fists on the cross. It clearly shows how the Chicanos expressed their inner feelings and translated them into a meaningful piece of art.

In Eric Avila’s analysis of Almarez’s work.. “In their subject matter, the paintings of Almaraz and Botello emphasize the dysfunction and unsightliness of freeways, contradicting the stated intentions and crafted visions of the Division of Highways.”s Black and Latino Angelenos in particular- expressed their opposition in cultural terms through art, literature, poetry, photography and other forms of expression. People living in East LA were deeply affected by the freeway because it was directly in front of them, in their face and had to contend with the daily roar of traffic. Chicano artists, like Almarez, Frank Romero, and David Botello began to incorporate this into their art, they painted stories of how these infrastructures impacted their lives and the implications of their intent. Murals and other forms of painting were used to critique the social and political forces being imposed onto these communities.

Carlos Almarez, Sunset Crash, 1982 (Artstor)

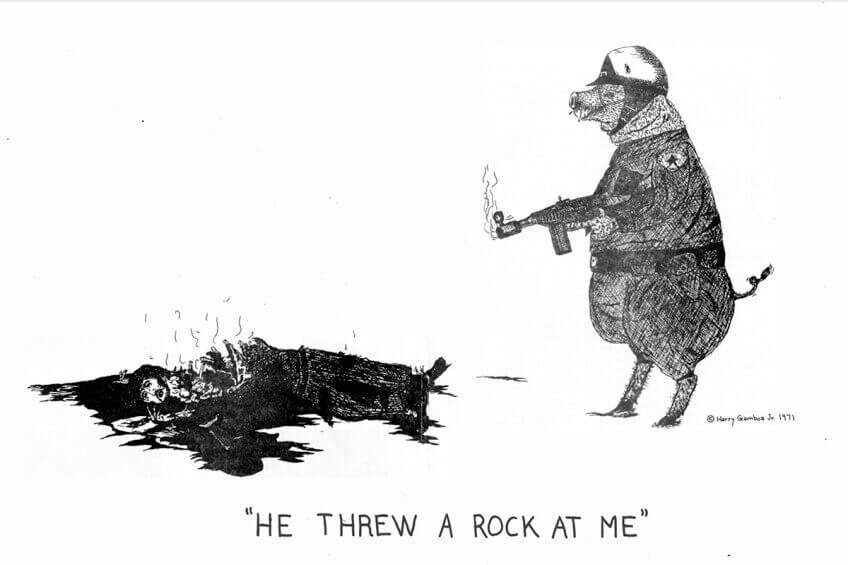

Artists and activists coming of age in LA in the late 1960s and 70s sought out avenues of political speech and self-expression in printed media as well as the visual arts. The Many Legacies of Regeneracion by Kevan Antoni Aguilar explores the impact and legacies of the revolutionary concept of "Regeneración" in the Chicano community and in politics and the arts.The concept was developed by Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magon at the beginning of the 20th century in Mexico City he word became a symbol of resistance, particularly in the political sphere, but also in a cultural sense. The brothers and their fledgling publication of the same name later fled to Los Angeles in 1910, escaping persecution by the Diaz regime. Their call for revolutionary change rather than reform impacted labor and anti-fascist movements in Mexico, the US, and Europe.While in LA, the Magon brothers continued their work in pushing for Mexico to reject the continued exploitation of campesinos by the regime and land owning elite, and “called on Mexicans both at home and in the United States to reclaim their country under the banner of “tierra y libertad,” or “land and liberty.” Regeneración, revived as a concept in 1970s Los Angeles, “proposed critical interventions on the impact of capitalism, imperialism, patriarchy and racism on the city’s Mexican-descended communities and promoted social revolution rather than political reform.” A publication titled Regeneración was revived by renowned feminist activist Francisca Flores and later by the art collective, Asco, “objected to the assimilation of Mexican-Americans into U.S. society and politics, the Asco collective railed against police brutality and the Vietnam War, while also calling for a critical race analysis within the second wave feminist movement.”

Harry Gamboa Jr. He Threw a Rock at Me featured in Regeneración (Los Angeles), vol. 1, no. 9, 1971.

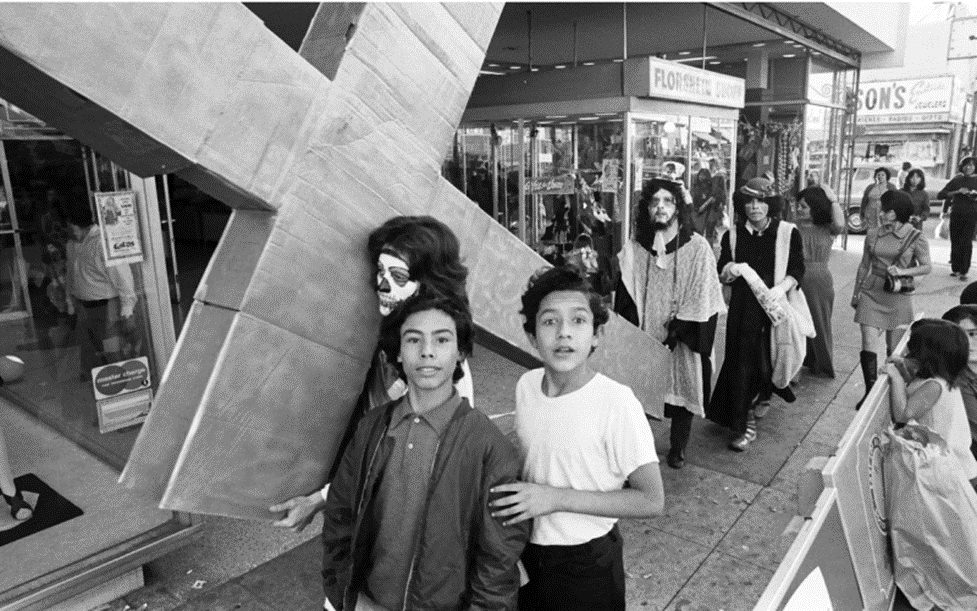

Ever expanding the dimensions of critique, one most notorious or infamous group within the Chicano art movement was Asco. A multi-media art group formed in the early 1970s. Original members, Harry Gamboa Jr, Willie Herrón, Glugio ‘Gronk’ Nicandro, and Patssi Valdez, sought to push the limits of art during a time of political unrest. Their work was often seen as provoking and repulsive, this impression giving them their name, Asco Spanish for “nausea”. The name also referred to the way they were perceived by conservative Mexican/Chicano community due to their avant-garde fashion. If one of them was “walking down the street with yellow eyebrows and fishnet stockings, someone’s mother would say ‘¡Hey, que asco!”They also produced many pieces of performance art. Bizarre public art installations that were often used hit-and-run tactiques to avoid arrests. These performances were often meant to draw awareness to violence facing the Chicano community.

Asco, Walking Mural, 1972 (Artstor)

“Ascos avant-garde strategies were "urban survival techniques that emerged from the organized protest movement against the use of Chicanos, and other people of color, As the literal avant-garde in the war in Vietnam” (Chavoya, 293). They created performance art shows that highlighted the deliberate erasure of Chicano culture in mainstream media along with responses to Chicano civil rights movements and police brutality against Black and Brown folks. Their most highlighted pieces of work were the “No-Movies”. This body of work consisted of post-modern visual pieces of art wherein the creators were poking fun at Hollywood stereotypes. In creating these photographic works, they highlighted their simultaneous disgust for and interest in the opulence of the commercialized, mainstream art produced by the film industry as well as underscoring the absence of any meaningful Chicano representation. Their aim was to use art to fight against racism in the media, police violence,and the Vietnam draft by producing pieces that used their native East Los Angeles as the backdrop for their performances and photography. Later identified as a pioneer of contemporary conceptual work, this artistic group was overall poorly received by the public and was largely left out of the record of art that helped shape the Chicano movement.

Asco, Stations of the Cross, 1971 (Artstor)

Community arts institutions emerged as vital spaces for organizing and education. In the video Entre Tinta y Lucha: 45 years of Self Help Graphics tells the story of the 45-year cultural journey of the legendary Los Angeles community arts organization Self Help Graphics and Art (SHG).SHG is a community arts organization in Los Angeles that has been helping Chicano/Latino arts develop for over 45 years.The mural movement of the 1970s was especially important because the movement brought art to the streets and showed that art could also represent the voice of the community. SHG redefined the way Chicano/Latino art was organized in the United States through innovative forms of screen printing, mural movements, and annual Day of the Dead celebrations.

Procession from Evergreen Cemetery to Self-Help Graphics during a Day of the Dead celebration 1976 (Calisphere)

For example, the groundbreaking Barrio Murals Movement of the 1970s transformed street art into a community power tool. Self Help Graphics has developed a large number of Chicano and Latino artists through innovative screen-printing techniques, helping them to incorporate social issues into their artwork. SHG organized Day of the Dead events that carry on Mexican culture in LA, and have become an important festival of unity and cultural identity for the Chicano community. SHG also helps artists create and also connect arts, writing, publishing, and social organizing to help Chicano communities build a cultural identity and support their social movements.

The Continued Struggle and Joy of Chicano Self-Expression

By Claudia Guzman, Jared Harris, Lam Tang

The Chicano journey is not only a process of bringing awareness to its people, but one of belonging. In the face of outward scrutiny, an erasing of their history, commodification of their culture through stereotyping, and an internal feeling of ambivalence towards their own existence, Chicano people have fought and fought again for their place in the world. This section focuses on how contemporary Chicano artists have kept this fight alive from the 1970s to the present. The way this movement was popularized was mainly through the medium of art. Public art such as muralism, performance art, and self expression such as dress and makeup, and private art such as photography, printmaking, and illustration were the main sources where Chicanos founded a platform to bring visibility to themselves.

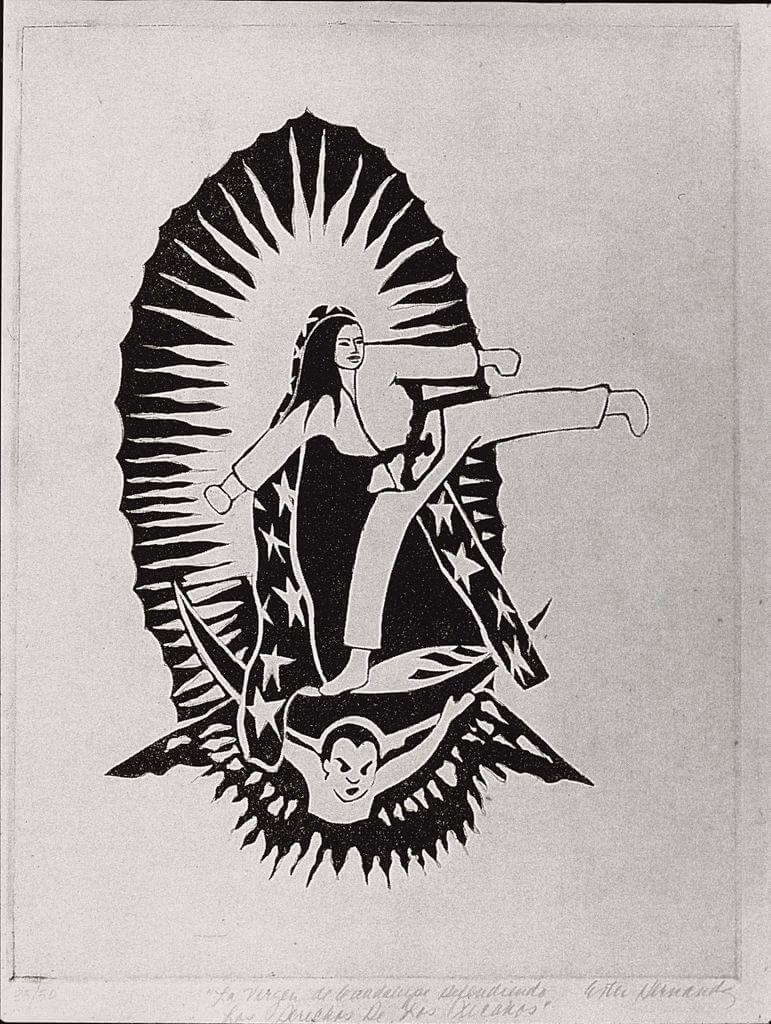

Ester Hernandez, La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Xicanos, 1976 (JSTOR)

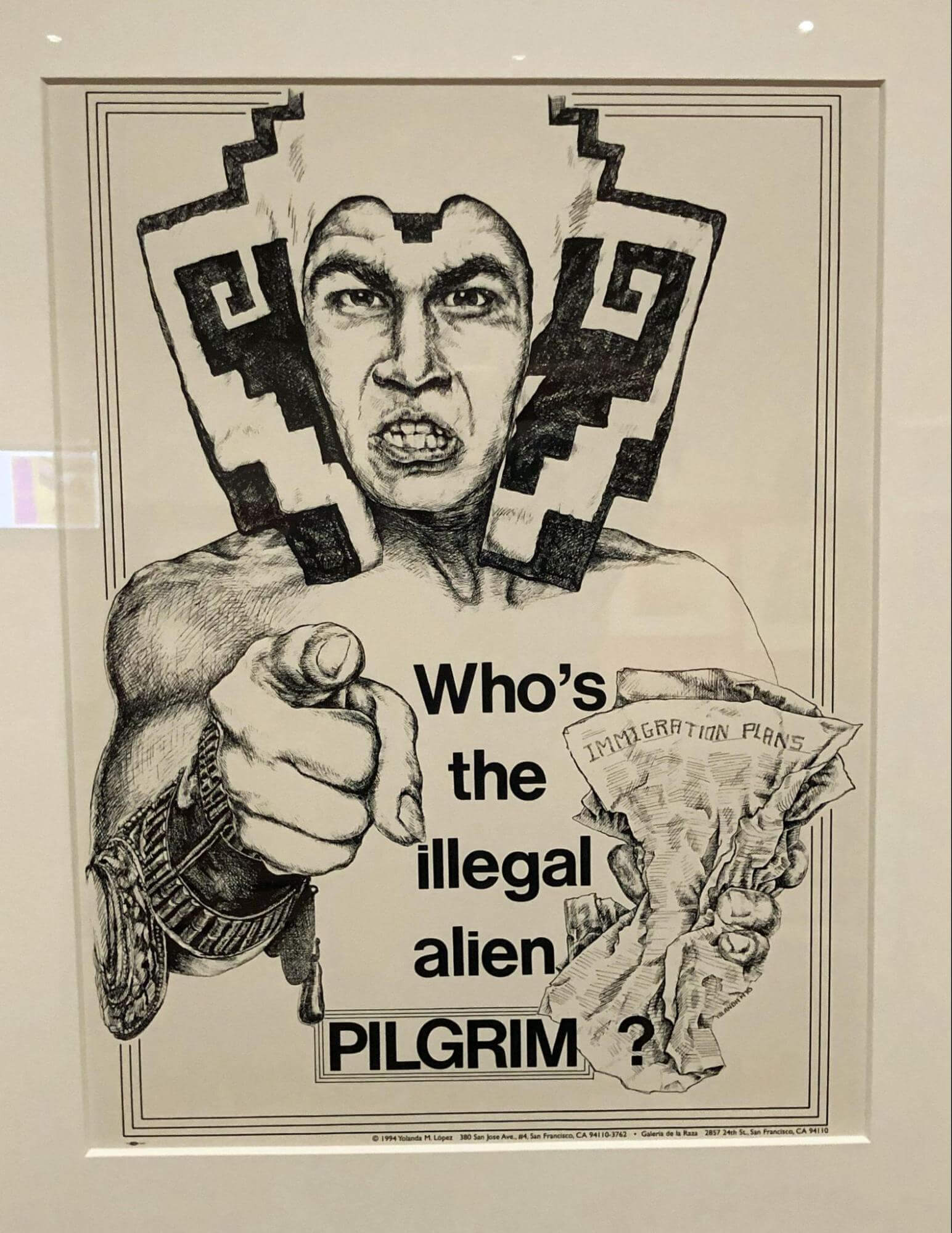

One technique in particular that was consistently used to great effect in this movement was the reimagining of cultural symbols to bring about a new narrative to Chicano history, symbols such as The Virgin of Guadalupe, The Statue of Liberty, Uncle Sam, iconography of the Mexican & US flags, and more saw their image change to bring new meaning and further the goal of bringing Visibility to the Chicano experience. For example Yvonne Yarbro‑Bejarano from the article Remapping America in Ester Hernandez’s “Libertad” and Yolanda Lopez’s “Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?” examine how Chicana artists Ester Hernández and Yolanda López use visual art to challenge dominant American cultural narratives and reassert Chicano identity. The piece critiques exclusionary definitions of citizenship and freedom, replacing them with a symbol that embraces Chicana identity and demands civic equality.

Yolanda Lopez Who’s the illegal alien, PILGRIM? 1981 Artstor)

Similarly, in the article “Painting a Place: A Spatiothematic Analysis of Murals in East Los Angeles” by Zia Salim, it dives into the thematic and spatial patterns of murals in East Los Angeles, which is a historic neighborhood that is significant to the Mexican-American community. Many of these murals contain a deeper meaning and can help show the community what message is being sent out into the world. The murals analyzed what different messages are being shown here such as religious identity, community origins such as ancestry roots, and the struggles they endured. A lot of these murals are shown on big commercial and residential buildings. They might even take up an entire wall of these buildings and are very captivating.

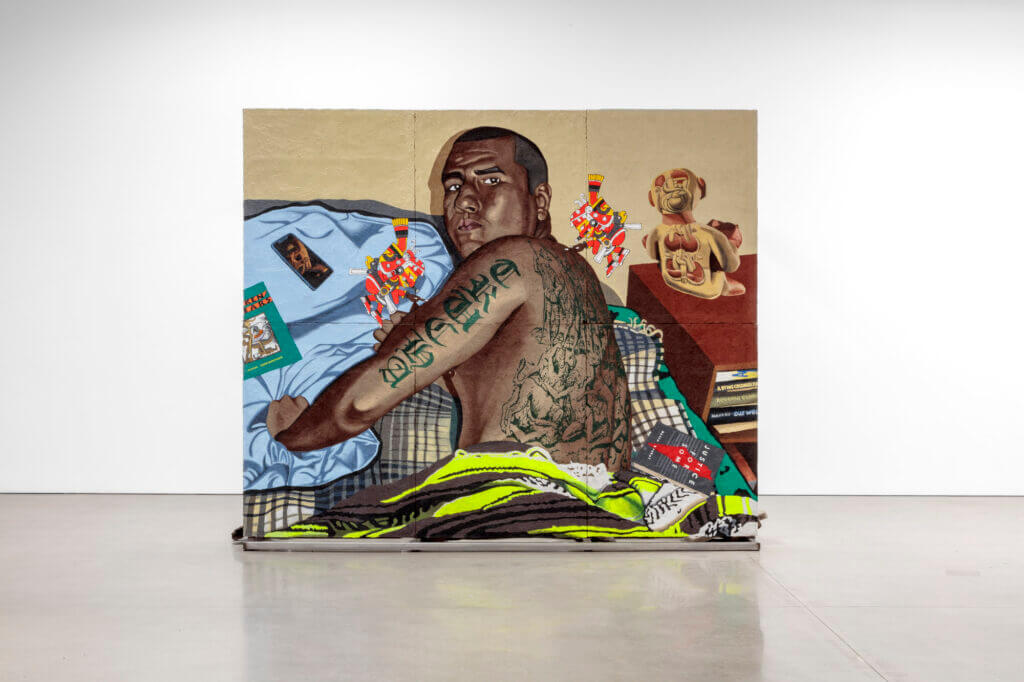

The documentary Arte Cósmico explores the work of six contemporary Latinx artists in Los Angeles: Rafa Esparza, Beatriz Cortez, Patrick Martinez, Guadalupe Rosales, Gabriella Sanchez, and Gabriela Ruiz. The episode showcases how these artists create “cosmic” spaces that link personal histories with larger social and political structures. There is a strong theme of recontextualization within the works, from school pamphlets, neon signs, family photos, and more that are used to bring visibility into the Chicano culture and subcultures that exist within that umbrella, such as the 1990s rave scene, tagging scene and low-rider culture.

rafa esparza, Trucha, 2024 (Artist’s Website)

Each artist has a vastly different approach to displaying their art but they all share a goal of bringing connections to one another within their communities and to show the rest of the world what Chicano culture looks, sounds, and feels, like. Gabriela Ruiz stated “There’s something really beautiful about seeing ancient peoples as your contemporaries and not being tied by time and space. Because time and space is something that's also linked to visas and documents and borders... and I don’t want my contemporaries to be defined by a border.” The representation of Chicano artists challenges dominant art narratives and asserts Latinx presence in both local and global art worlds.

Gabriela Ruiz, Full of Tears, 2019. (Artist website)

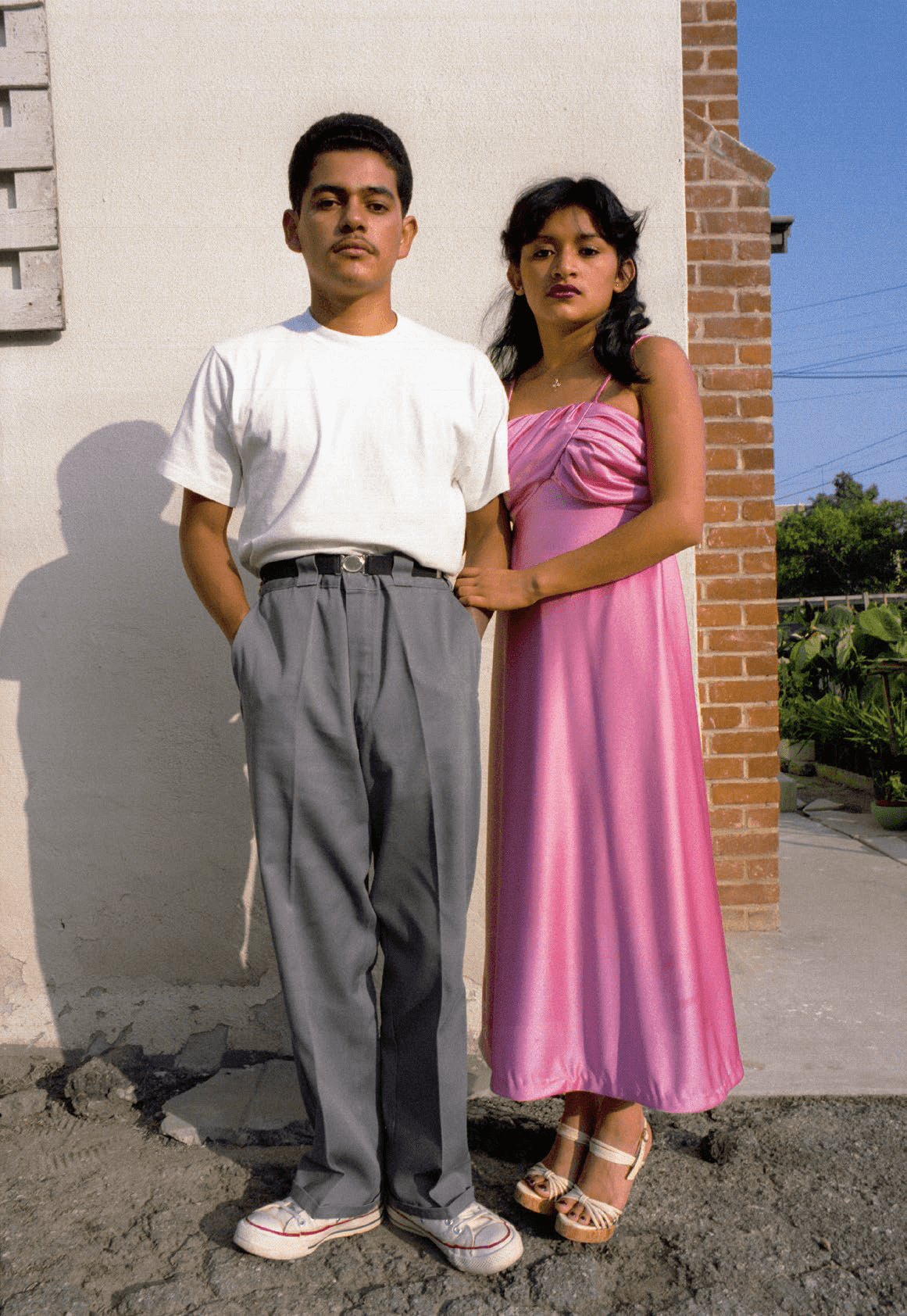

By keeping the art of the Chicano Rights Movement alive, contemporary Chicano artists continue to bring visibility to their people and their histories and are able to foster a space; be it physical or mental, where they can truly belong. This sentiment is emphasized in the article “You Belong Here,” in which Pilar Tompkins Rivas reflects on the power of Latinx photography to preserve identity, family history, and cultural memory in the United States. Rivas captures the need for a broader, more inclusive visual archive that reflects the multiplicity of Latinx experiences that range from military service to fashion to activism, and home life.“They are records of our presence that collectively chart the paths and routes of Latinx people - from whom the border crossed generations ago to those who cross the border today.” These stories are often looked over or downright hidden from the public sphere and through sharing this collection of photos the author hopes to bring more visibility into these Latino people’s lives. This article proved to be very moving when it came to seeing just how ingrained Latino culture is with American culture and how grievous it is that America tries to “otherize” this group of people.

John Valadez, Couple Balam, 1978 (artstor)

In Phantom Sightings, the exhibition shows how artists navigate being “Chicano” without being boxed in by it. Rather than rejecting identity politics outright, the exhibition wrestles with its limits, using it as a lens to examine institutions, media, culture, and art itself. It’s not just about representation, it’s about critique, resistance, and redefining the terms altogether. As suggested in Regarding Family Photography in Contemporary Latinx Art by Deanna Ledezma, there are a lot of misunderstandings about Latinx culture due to people outside the community not being educated or exposed. Instead of worrying about what others may think and say, these artists challenge stereotypes, and stigmas. They do this by putting art out, because it's hard to deny someone's perspective or truth.

In 1972, the art collective ASCO tagged the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with their name in response to a LACMA curator’s dismissive statement that Chicanos made graffiti not art, hence their absence from the gallery walls. As many of these articles touch on, the notion of “including” Chicano artists in temporary exhibitions does little to address the longstanding structural racism endemic to arts institutions and academies, and rather often reflect continued colonial-style extraction of cultural and economic value momentarily commodified to benefit a museum, gallery, or scholar. As the commissioning, censoring, and deportation of David Siqueiros in the 1930s demonstrates, LA’s civic and arts elite time and again expect Latinx artists to fall in line and embody their identity according to their narrow and self-serving expectations. Art collector and comedian Cheech Marin perceived this longstanding institutional lack and used his economic and cultural clout to open a museum of Chicano art in Riverside.

Asco, Spray paint LACMA, 1972 (Artstor)

By artists not holding back, and deciding to put out art; it allows for people to view a different perspective or even one they relate to. That's why it's important for oneself to be expressive, to expose others to their truths and realities. People don't have to understand or love it, yet the exposure helps create the discussions necessary to push or lead to different realities for future generations. Each of these collections of contemporary art illustrate the difficulties of expressing the Chicano identity and share the goal of bringing visibility to Chicano communities and individuals and through their induction to the public consciousness they are able to make room for a group of people who are often not thought about in American culture or outright removed from it.

Muralism and Public Art in Los Angeles

By Isaiah Mitchell & Anna Kryczka

The tradition of public art and muralism in Los Angeles came to civic and community prominence in the 1930s and is deeply connected to the Mexican Revolution. The goals of the revolution were rooted in a critique of Porfirio Diaz’s corrupt and dictatorial rule and called for equitable distribution of land, an end hacienda servitude and an end to foreign land ownership and exploitation. During the political consolidation of the Mexican revolution, President Obregon appointed Jose Vasconcelos as secretary of education. Vasconcelos saw public art and in particular muralism as vital tools for the construction of modern Mexican identity. This notion of mobilizing public art to communicate political ideals and identity caught the eye of a friend of US president Roosevelt who wrote to him with excitement: “The Mexican artists have produced the greatest national school of mural painting since the Italian Renaissance. Diego Rivera tells me that it was only possible because Obregon allowed artists to work at plumber's wages in order to express on walls of government buildings the social ideals of the Mexican.” In the throes of the great depression, Roosevelt launched the Works Progress administration which would come to employ thousands of artists in the creation of public works of art.

Jose Clemente Orozco Prometheus, 1930, Pomona College. (Artstor)

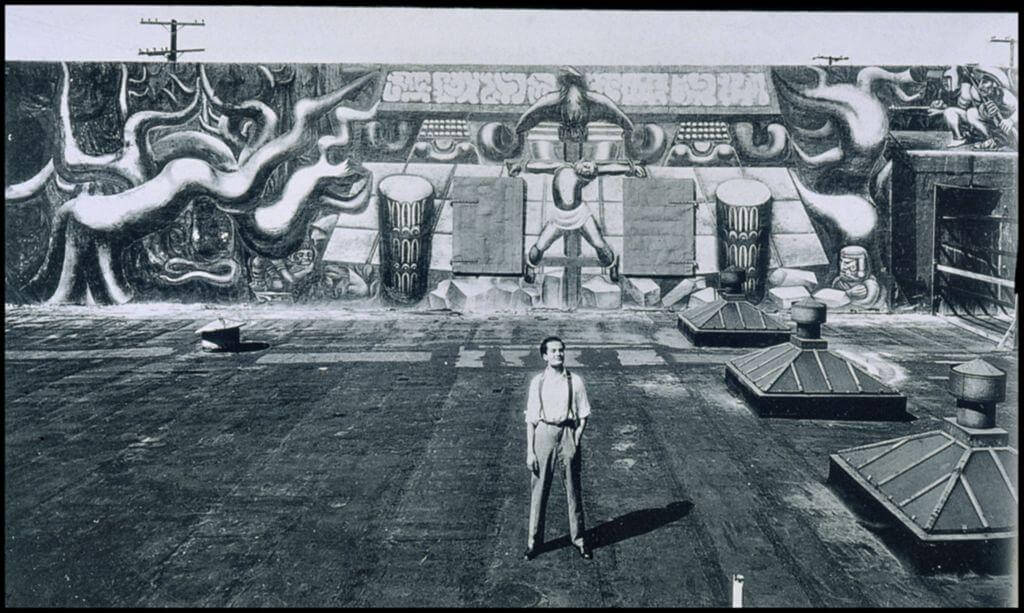

Renowned Mexican muralists Rivera, David Siqueiros, Jose Clemente Orozco and others traveled to the United States to create work and train artists. Here in Los Angeles, Siqueiros was commissioned by the Anglo elite to create a mural titled America Tropical on Olvera Street, as they worked to illegally displace a vibrant residential Mexican and Mexican American neighborhood to create a whitewashed tourist trap offering “a touch of old Mexico.” Intended to be a mural depicting the verdant natural beauty of an idyllic Mexican landscape to fit, Siqueiros defied the request and created a damning indictment of US imperialism in Latin America and mass illegal deportations of Mexican and Mexican Americans that displaced hundreds of thousands of Angelenos. Of his work Siqueiros stated: “It is the violent symbol of the Indian peon of feudal America doubly crucified by that nation’s exploitative classes and, in turn, by imperialism. It is the living symbol of the destruction of past national American cultures by the invaders of yesterday and today. It is the preparatory action of the revolutionary proletariat that scales the scene and readies its weapons to throw itself into the ennobling battle of a new social order(443).” He rebelled against the government by not catering to a whitewashed interpretation of Mexican culture, and in turn faced whitewashing and censorship. He also focused on Mexican struggles and cultural resistances in relation to the American cultural and political landscape. The mural was censored, painted over, but not destroyed, and Siqueiros himself was deported. The white paint used to censor the mural began to peel off in late 1960s and a massive Chicano community led and later Getty Institute funded effort to restore the mural, its history and legacy was undertaken.

David Siqueiros in front of his mural America Tropical on Olvera Street, 1932 (Artstor)

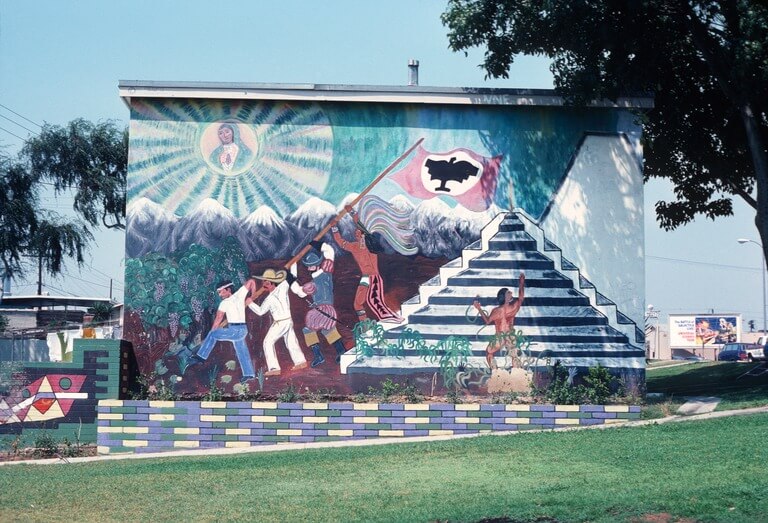

In the late 1960s as the Chicano Rights Movement emerged in LA, public art and muralism became a vital avenue of political and cultural expression. Using visual expression as a way to reject the feeling that anthropologist Carlos Vélez-Ibáñez has described as existing as, “not only strangers in their own land but strangers to themselves,” the mural practices emerging in the early 1970s emphatically stated the presence and pride of the Chicano community. The murals located in places like Boyle Heights and East L.A. give a meaning to the culture, history, and struggles of these neighborhoods through public visual art. Art Historian Shifra Goldman refers to murals as “the billboards of the barrios,” highlighting their ability to communicate directly with the community in a manner that is both assertive and visible. In Los Angeles, these murals provided Chicanos with a platform and a means to express their presence in a city that has not acknowledged their worth. These murals give a sense of visibility, acknowledgment, and connection to their heritage.

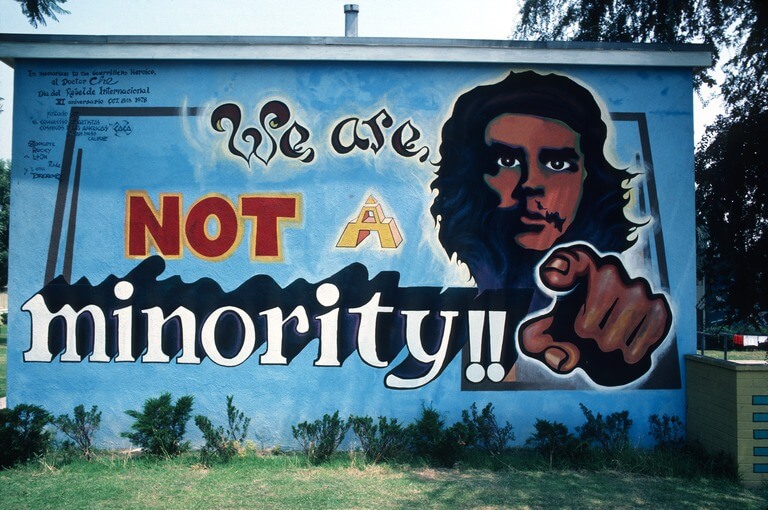

Mario Torero, Rocky, El Lion, and Zade, We are Not a Minority at Estrada Court, 1978 (Artstor)

In Marcos Sanchez Traqulio’s essay he focuses on the young Chicano’s use of the graffiti in East Los Angeles, and their use of graffiti to better understand their identity of themselves. For this essay Tranquilo decided to focus on the art located in Estrada Courts because of its impact on Chicano art in East Los Angeles. East Los Angeles being known for its high population of Mexican Americans are a prime spot to locate art of young Chicano children. However, it is also known for its gang violence because of a largely marginalized group of people, which can be seen with many of the children in Estrada Courts. While observing the graffiti in Estrada Courts it was used to make territories of certain groups, making people aware that they were entering the area of specific gangs. This graffiti was used to help create a sense of identity for some youth as it helped them understand who they were associated with and the territories they could and couldn’t be. However the art became more complex over time, due to the mural art program directed by Chalres W. “Cat” Felix. With this new art program young aspiring artists would learn to create more complex pieces, and would find themselves a new identity in artists and not gang members. “The young adults provided leadership at Estrada Courts had survived the destructive youth gang lifestyle and were intent with redirecting lives of active youth gang members in more positive directions through Mexican American and Chicano carnalismo (neighborhood or group brotherhood)” (Sanchez-Tranquilo). Art was a new outlet for young Chicano children as it allowed them a new path in life not associated with the gang lifestyle.

Alexandro Mayo, Tribute to Farm Workers at Estrada Courts, 1974 (Artstor)

In Mexican American Exterior Murals, by Daniel Arreola, he highlights how murals are used to create change, and represent cultural heritage and preferences. Over the years since the 1960s, mural painting became a tradition to Mexican Americans, with it being prominent in their communities. For example, murals can commonly be seen in restaurants and on buildings. Murals are also used as a form of political expression, with the increase of ethnic awareness bringing mural painting to cities all over America. Murals were painted in areas of large social gatherings to ensure messages were being conveyed to local communities.

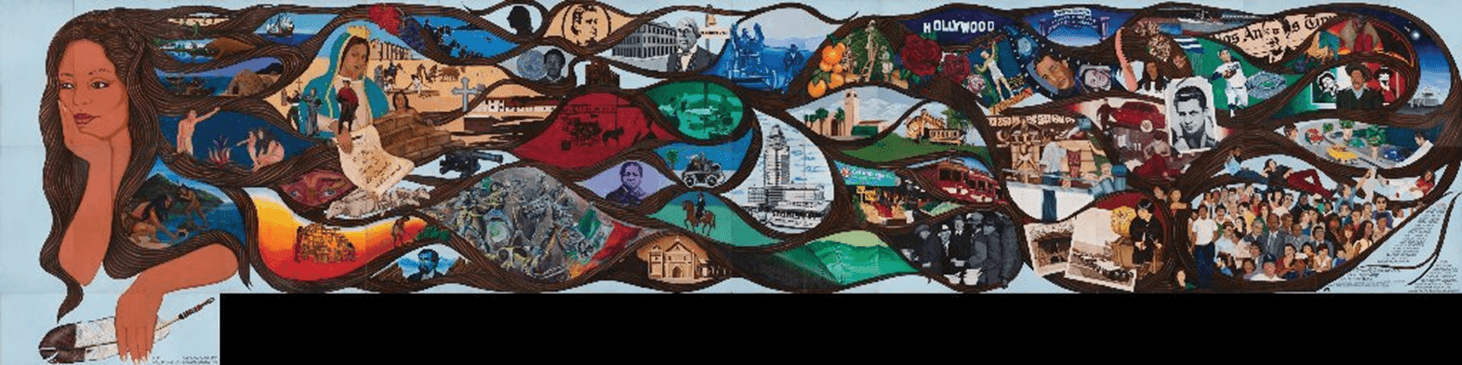

The acknowledgement of muralism as a vital form of expression in Los Angeles led to civic interest in commissioning public works of art in the early 1980s, as the city prepared to host the Olympics. In 1981, Barbara Carrasco was commissioned by the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) to create a mural for the city’s bicentennial. Carrasco’s mural “LA History: A Mexican Perspective” was rejected because the Agency deemed many scenes too controversial to display. Inspired by the history of Los Angeles, Carrasco would engage in research for months to find what best represents the city. After going through the archive of the Natural History Museum, Carrasco set on doing a mural on fifty one vivid scenes throughout the history of Los Angeles planted into the flowing hair of a brown-skinned woman resembling her sister. She worked alongside a group of young artists from Los Angeles County’s Summer Youth Employment Program. The mural showcased the city’s diversity including scenes of the Japanese Internment camps, Chinese immigrants constructing the railroad, and the displacement of many families from the Chavez Ravine to make way for the construction of Dodger Stadium. Carrasco refused to remove the “controversial” images when prompted by the CRA executives. She was forced to store her mural in Caesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers Headquarters. The mural has since been restored and installed in the Natural History Museum’s new lobby.

Barbara Carrasco, Barbara Carrasco LA History: A Mexican Perspective, 1981(Artstor)

In Whose Monument Where: Public Art in a Many Cultured Society, muralist Judy Baca highlights how public art focuses on the majority, while existing in spaces of diversity. Baca emphasizes how public art paints a surface level picture, which creates a false sense of identity, representation,and inclusion. Reflecting on these issues in 1995, Baca determined that artists should use their communities to promote real unity and change, rather than leave it up to the “developers” to act on their agenda or if artists deviate from those goals, their work is censored as we saw with Siqueiros and Carrasco.

Judy Baca and Social and Public Art Resource Center, The Great Wall of Los Angeles, North Hollywood, 1976-1984 (Artstor)

As we reflect on community-driven and civic-commissioned public art in Los Angeles, we see a long and complex history of attempted exploitation and censorship met with rebellion and declarations of expressive autonomy and deeply localized forms of cultural identity. Baca statement of the power of public art connects to the effort to restore the history of the Guillermo Martinez’s work, she states: “Socially responsible artists from marginalized communities have a particular responsibility to articulate the conditions of their people and to provide catalysts for change, since perceptions of us as individuals are tied to the conditions of our communities in a racially unsophisticated society.”

The purpose of a visual analysis is to describe and interpret the visual choices the artist made in creating a work of art. Observing and writing about a single work of art requires intensive focus on the work's visual attributes, like color, line, scale, and composition. This visual description builds towards an evidence-based interpretation of the meaning of the visual attributes to both the artist and the author of the analysis.

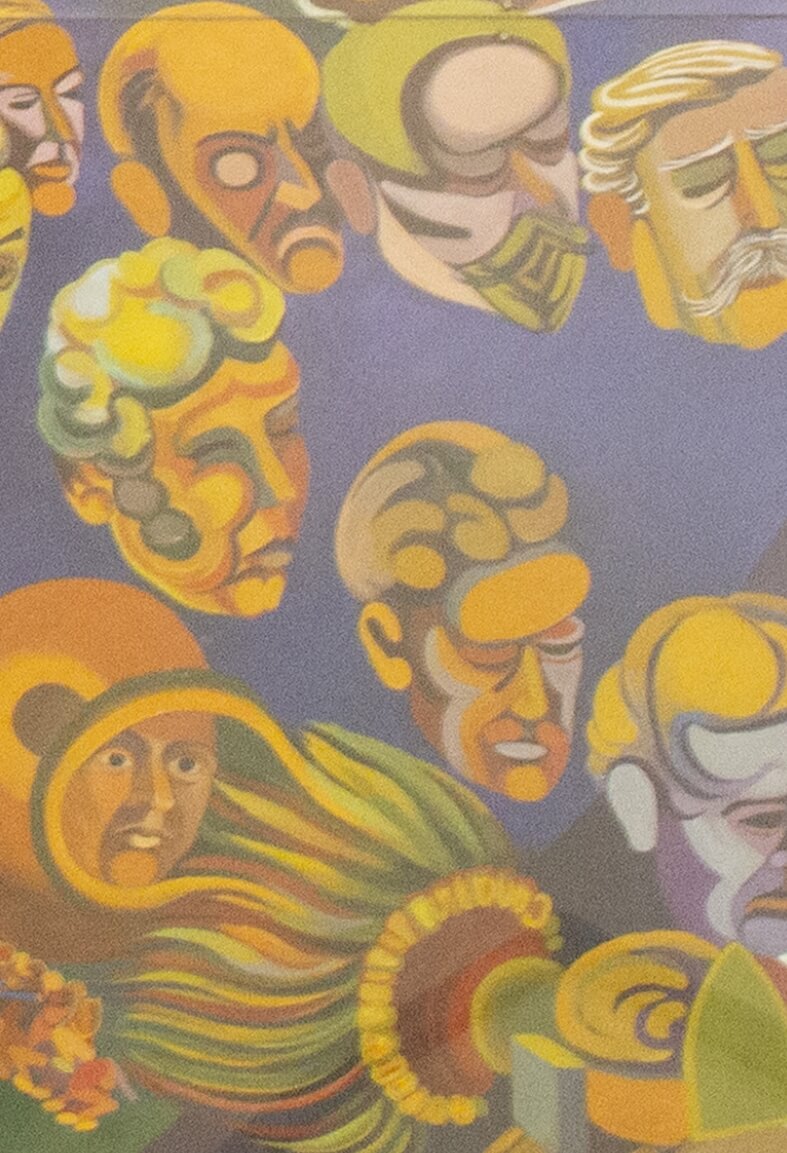

The Chicano Mind (1973) by Guillermo Martinez is a powerful and culturally rich mural located in the southwestern stairwell of Pasadena City College’s C Building, between the 2nd and 3rd floors. The mural serves as a vivid expression of Latino cultural identity, resilience, and community pride. At the center of the composition stands a Chicano man posed in a Christ-like stance, directly confronting the viewer. To the viewer’s left, the man’s right wrist is nailed down, and a red rope is wound around his arms, clutched tightly between his fists. Unlike the traditional crucifixion pose, his arms angle diagonally, suggesting the outstretched wings of an eagle struggling to rise. Surrounding the figure, beneath his arms, and arching above his head is a diverse assembly of faces, painted in muted colors with hollow, empty eyes. These faces represent a broad spectrum of identity, reflected in their facial features and attire. Some wear indigenous garments, others don sombreros, American clothing, and various culturally significant outfits. Among these are several eccentric and surreal faces, which I will explore in detail later. Above the central figure’s anguished face is a circular emblem adorned with imagery drawn from the American flag, including stars, stripes, and patriotic colors. Beneath the figure reads the phrase “VIVA LA RAZA”, rendered in bold, colorful symbols. The entire scene is set against a dynamic, asymmetrical background of spiraling red and white stripes from the American flag, interwoven with Aztec and indigenous Mexican patterns. Ultimately, the painting is a very symbolically rich and powerful exploration of Chicano and Mexican-American themes.

In this analysis, I will explore the mural’s central imagery, visual details, and symbolic elements to better understand how Guillermo Martinez uses art to convey resilience, cultural pride, and protest against oppression. I will also reflect on how the mural’s message resonates with ongoing struggles faced by Latino communities today and how it impacted me as both a viewer and a student.

To begin my analysis, I will speak on the central figure which dominates the mural. The Chicano man in the center in a Christ-like pose immediately signals the mural’s themes of suffering and resistance. By referencing such a loaded religious image, Martinez invites viewers to consider the historical role of martyrdom in both religion and social justice movements. However, this figure is not a passive victim. The diagonal positioning of his arms and the tightly clenched fists gripping the red rope suggest an active struggle against oppression rather than quiet submission. The rope between his hands showcases the idea that though the man may be oppressed he still carries his own lead. The implied motion in his posture, reminiscent of an eagle attempting to ascend, connects directly to Chicano cultural symbols of freedom and resilience. This image, often associated with indigenous Mexican mythology and Chicano activism, transforms the figure from a mere martyr into a symbol of defiance and survival.

Another striking detail is the partially exposed organs visible within the figure’s torso. This detail adds a visceral element to this painting which works to depict how intense and consuming the struggle for cultural survival and self-determination can be, suggesting that the fight for identity is not only external but also tears at the body and spirit from within. Through this portrayal, Martinez critiques both historical and ongoing attempts to restrain Chicano communities, while also affirming their enduring strength and refusal to be erased.

Surrounding the central figure is a ring of faces that blurs the boundary between past and present, reinforcing the idea of generational struggle and solidarity within the Chicano community. Each face, rendered in muted tones with hollow, vacant eye sockets, represents different cultural identities and eras. Some wear indigenous headdresses, others don sombreros or contemporary American clothing, while a few verge on the surreal, suggesting the effects of cultural assimilation and loss of identity. The most prominent of these surreal faces is one covered in stars, with stars for eyes and stars composing its head. This striking image symbolizes how individuals can become consumed by American culture to the point of losing their sense of self, a powerful commentary on cultural imperialism and erasure. Alongside it, two other abstract, dehumanized figures made up of geometric shapes float above the man’s head, further emphasizing the danger of losing humanity and individuality in a system that strips people of their cultural roots and history. The empty, hollow eyes of the surrounding figures evoke a haunting, almost ghostlike presence, as though these faces are ancestral spirits bearing silent witness to both past and present injustices. The hollow eyes could also represent the loss of humanity of many Chicanos throughout the years, and how oppression has led them to lose their sight. This is a reminder that the fight for cultural identity and justice has always been, and continues to be, a collective one. By encircling the central figure, Martinez visually situates today’s struggles within a long, unbroken lineage of resistance and survival.

In conclusion, the mural The Chicano Mind by Guillermo Martinez stands as a powerful testament to Chicano resilience, cultural pride, and generational solidarity. The mural’s blending of American flag elements with Aztec and indigenous patterns visually captures the complex negotiation between assimilation and cultural preservation that defines the Chicano experience. I found this tension deeply resonant, reflecting ongoing battles for recognition, justice, and belonging in a society that too often marginalizes indigenous and Mexican-American histories. I walked past this mural for years without a second thought, but while analyzing and engaging with the artwork, I was struck by how much insight awaits us in art and the world around us, if only we take the time to pay deeper attention. I am reminded of the importance that many Chicano activists have voiced for decades: active engagement, critical reflection, and action as essential for preserving cultural identity and confronting injustice. The beginning of doing what is right is paying attention, and Martinez’s mural serves not only as a historical statement but also as a living reminder to honor the struggles of those who came before while remaining committed to the work that still lies ahead.

This visual analysis report will be about The Chicano Mind (1973) by Guillermo Martinez located in the C Building of Pasadena City College. At first glance, the painting can look overwhelming because of all the designs and the different colors used. It gives an anxious but curious feeling to its viewers. As a PCC student, I have passed this painting many times and I never realized how much detail it has and the story it’s telling. Every painting in history has a significant story to it and it takes extra time for a person to analyze what the artist could have been trying to say.

When looking at this specific painting, the biggest part of the piece is at the center which is showing a shirtless man with a look of agony and anger. At first glance of this man, it looks very similar to the image of Jesus Christ on the cross which is a very important image for the Catholic church. The Catholic church has the most people who practice the religion and the majority of the people involved in Catholicism are of Hispanic/Chicano descent. This brings me to the surrounding images in the painting, which include a wide range of people’s heads. The other people shown in the painting on the top and left side of the Christ-looking man appear to be Hispanic. They all have characteristics of a Hispanic individual such as a mustache, long thick hair, and sombreros.

The entire painting has many significant aspects that are sending different messages all around but, the most powerful part of the piece to me is the different people shown on each corner as I previously mentioned. On the left bottom corner, it shows a group of Hispanic men who appear older, maybe around their 50’s–60’s. They could be representing farm workers because a few of them are wearing sombreros. This can be because of how much work these workers would put in a day when working these hard labor jobs when many of these Mexicans migrated to America in the 19th century after the U.S.–Mexican War and during the Gold Rush in California. Since America saw how desperate they were for jobs, it could have been the reason they were given the hard labor jobs.

Above the first group of people there is another circle of people shown and they appear older. They might be representing the older generation of Hispanics who have encountered hardships as well and possibly discrimination. The majority of the figures in this circle of the painting are also wearing sombreros and the women are wearing head covers as well. The top group of people in the painting are shown in a brighter green and are all looking in the same direction, which can show them as brave and a leader of something. One of the people shown looks very similar to Cesar Chavez, who was an important part of Chicano history when the labor laws were insufficient. There is one figure that has facial features but is covered by many white stars and a few hints of red and blue, which could be showing an American individual. They might have been painted this way because the artist wanted the Chicano figures to appear more important.

The other group of figures on the top right corner all appear to be powerful, Hispanic men. They can be representing leaders of many Chicano movements in history. On the bottom right corner, the figures seem to be showing mostly White Americans due to the facial features and the accessories they have. A few of the heads are wearing a military hat and this could be representing the men who had to fight in wars such as WWI and WWII. The other figures appear to be older, perhaps people who represent the American Congress or Government. These people are significant because they were responsible for importing different labor laws and limiting the Hispanic community from liberation. Each one of these figures might be representing different races and what role they played in this historical time.

The man in the middle as I previously mentioned seems to be representing a possible Chicano man who might feel distraught with all of these different people wanting to influence him or control him. There are also many fists pointing outwards in different colors and a fist can usually mean a sign of power. As a student looking more into the details of this piece, I realize that it does have significant meaning to the Chicano/Hispanic community and their history. I consider myself a part of this community because of the culture I grew up in and where all my family is from. In today’s society, the Hispanic community might have similar feelings of being excluded or controlled because of their race and I believe the figure in this painting was supposed to represent that since our government can change our laws or rights and it can feel scary to be a non-white individual living in the United States.

Overall, the painting is really beautiful and does catch the attention of anyone who walks by it.

The Chicano Mind is a work of art by Guillermo Martinez. It is located in the C Building at Pasadena City College and was created in 1973. You can easily spot it as you walk up the stairwell onto the 3rd floor on the west side of the building. This mural evokes a lot of emotion as soon as you lay your eyes on it. The piece itself is that of a struggle experienced by the Latino community in America—of a troubled mind struggling to find their place, the generational trauma that is passed down, and attempting to release oneself from that.

At the center of the mural is a man painted onto the canvas in circular strokes, the style of the piece itself is common in Latino Muralism. His arms are stretched out upwards to either side, appearing to be bound and as if he is attempting to release himself from being bound, evident by what appears to be ribbon spiraled around his arms, loosening. The look on his face is that of anguish, either as a result of being restrained or from an internal battle to free himself of what is hindering him.

Both of his fists are clenched and on one of his arms, there are multiple fists shaping the silhouette of the arm, all of them also clenched. I believe this emphasizes the weight of the internal turmoil the main character of the artwork is experiencing and the anger and frustration he is feeling. At the same time, the fists could also symbolize resilience and strength. The man’s torso is also illustrated—it is naked, but not only showing skin, his insides are also exposed symbolizing his vulnerability and the baring of his soul.

Above his head is what looks like an extravagant circular crest. It is adorned with the design of the American flag all throughout and especially around the border of the crest. In the center it appears that there is a hand holding a sword and penetrating an abstract figure that is laid upon the American flag. I feel that this symbolizes how one can surround themselves and build a life upon typical American ideals; so much so that it will eventually feel as if they are imprisoned, and it’ll still never be enough—they will never be American enough. The very same society that one has conformed to will still stab you in the back.

Furthermore, surrounding the man are various heads. These heads are wearing sombreros, field hats, and headdresses, all with facial expressions that appear to be anything but happy or content. Their facial expressions are largely stoic, but a few appear to be angry or in despair. Because of this, I feel that these heads symbolize the generations of Latinos that came before the Chicano main character of the piece, and I believe they are putting an emphasis on generational trauma.

Generational trauma has a tremendous impact on the way one leads their life and it is extremely hard not to pass it on. It takes a lot of effort to break free of it and the internal struggle is extremely exhausting and debilitating. These heads of past generations in the mural all had the same struggle—it was experienced differently in a way that was unique to them, but it is something that was strong enough to persist throughout an entire bloodline. Generational trauma in Latin American communities has themes of oppression, financial struggle, limited opportunities and resources, and how it affects several areas of their lives.

Breaking free of this would mean to change the trajectory of one’s life, of what has already been laid out for you. It means saying “no” and going against the grain, forcing yourself into a different mindset and working hard to be “better” and to succeed in areas that generations before you weren’t able to. It is one of the hardest things a person can do, but it is worth it to ensure that you and the generations that come after you have a better quality of life.

As a Mexican American myself, I resonate with the message of this mural deeply, and feel that I could tell what it was attempting to convey almost immediately. There is so much pain passed down from generation to generation that is hard to overcome and that is a result of a lack of opportunities due to systemic oppression. The mural is extremely moving and motivates me to keep working hard at pursuing a career that will bring my dreams to fruition. It also motivates me to prioritize my mental health since that is something that is often ignored or denied in Latino communities and swept under the rug when brought up.

I am very passionate and very appreciative when it comes to my culture—I absolutely adore it—but I am also able to recognize how much work needs to be done to create a healthier environment for generations to come.

The Chicano Mind (1973) by Guillermo Martinez is a large-scale piece, depicting an artistic vision of Chicano history. The mural, with its use of repetition and wide color palette, tries to capture Martinez’s feelings on the subject. Pride, pain, and the weight of history can all be seen in this piece.

The piece has a radial white and red striped background, on the left half of a circle can be seen with a repeated pattern in hues of green and yellow. The main portion of the mural depicts a large circular disc with a figure in the center, holding his arms out. At the end of each arm is a repeated line of fists that stretch to the end of the mural. A snaking line of heads surround the figure, all different in color and in facial features. Above the figure sits a smaller circle, the border made up of holding up flags and playing American flag decorated drums. In the lower left of the border is an eagle holding a snake in its mouth, while figures in the center fight. Below the center figure are the words “Viva La Raza” spelled out by soldiers on horses, meaning Long Live The Race.

As stated before, the mural shows a circle above the center figure’s head, depicting a fight between two forces. The two sides can be deciphered to be America and Mexico. Drummers with large red, white and blue top hats stand on the bottom half of the circle. While a figure with endless arms holding up a white flag with a blue star, red and white striped fabric draping from their arms outlines the top half. On the inner border are soldiers with guns drawn, gazes focused on the center battle. Men in red, white and blue attire invoking the image of Uncle Sam fight with men in brown suits with wide sombreros. One of the American soldiers hoists two guns in the air while another tackles a man to the ground and the center stabs a man in the back. Martinez conveys this message of the dueling countries the clearest with his depiction of the Mexican coat of arms, whose symbol can be seen in the bottom left of the circle. The eagle sits perched in its matching brown hues wearing a sombrero, the Mexican flag draped across its back. In one claw it holds a guitar, while the other, along with its beak, holds a snake. While the eagle holding a rattlesnake in its mouth is the Mexican coat of arms, this snake has a unique appearance. It has alternating red and white stripes and bears a matching top hat. This excess of violence depicted in this section of the painting shows the brutality that the United States has inflicted on Mexico. While the American soldiers hold the upper hand on this battle, the people of Mexico have not given up on the battle, throwing back punches and not relinquishing their ground. There is a spirit of resilience displayed, one that can be summed up by the single image of the Mexican eagle eating the American snake.

The figure at the center of the mural stands with his arms extended, his head tipped back in pain as he clutches his fists. A long red string drapes from one hand to the other, tangling around the torso. With the use of line and color the body looks like it is stripped to muscle, his organs sticking out of his stomach. The pose itself is invoking a Christ-like figure, the man with his arms raised out, clad of any clothes, his face in pain as a nail impales his wrist.

Surrounding the center figure on either side is a twisting line of faces. The lines extend from the top of the mural to the bottom. The wide range of color comes back into play in this portion of the art, the faces beautifully rendered in shades of blue, green, red and yellow. This parade of faces gives the viewer a lot to take in; we can see many invoking images of the past. The face closest to the viewer is wearing an Aztec headdress, a few behind we see one wearing a morion. Further back we see a group of men in soldier hats. On the right, faces of men with their deep brown skin, large hats and dark mustaches. A decorated skull is shown in the upper left. It’s of interest to note that only two faces seem to be depicted as having eyes, the figure with the Aztec headdress and the one behind it in a shell-like helmet. The rest of the heads are depicted with black eye holes, making one view them like masks. It makes the viewer think about the Mexican “lineage” spanning different years, backgrounds all in conflict but all connected to the history of the land and its people.

Martinez’s mural is a vibrant piece that strongly utilizes repetition to speak to the viewer. Despite the chaotic impression one gets initially, looking deeper into the work one can see the themes of the Chicano movement valued by the artist. The central figure embodies the complexities of being a part of the Mexican-American-mixed Chicano culture and acknowledging there is a pain that comes with being a part of this history but also highlighting there is a pride and resilience in it.

The Chicano Mind (1973) is a painting by Guillermo Martinez that illustrates Chicano resilience and power amongst state oppression. Situated in Pasadena City College’s C Building, its wall-length size is a testament to its immense significance and purposeful assertion of Chicano presence. It depicts a presumably Chicano, Mexican-American man naked and tied by ropes, a nail to his left arm, and a crown. He powerfully strives and fights these restraints for the relinquish of control and for his autonomy and freedom. His fists repeat, circulating the painting, as if to convey “the fight.” Around him, circles of Mexican people gather, some in Indigenous attire, some in Mexican-American stylized outfits, professional dress, etc. (all are representative of Chicano pride, respect, and tradition). At the bottom of the painting reads “Viva la Raza”—a historical protest statement in Spanish that translates to “Long live the people,” meaning long live the Mexican people and their livelihoods. Furthermore, the painting showcases multiple references to the American flag, especially in reference to an Indigenous woman and with a Mexican flag. Ultimately, the painting demonstrates Chicano power, resilience, and self-determination.

First and foremost, the detailing of this restrained Chicano man is quite central to the story-telling of this painting. The audience can view what is assumed to be his organs through this style of drawing—this reflects the fight of the whole body and soul, and the idea of breaking apart while staying together with the strength of your ancestors’ work before you.

The combination of the nail and crown upon this man signifies the comparison of the Chicano man to Jesus Christ—depicting Christian and Catholic imagery. This imagery could have a variety of meanings; for example, it could imply that the Chicano man is targeted by the state and violently pushed into repression. It could also be an allusion to the widespread religious beliefs of Chicanos in Christianity and Catholicism—either under the guise of martyrdom and admiration or as a historic allusion to the brutal colonization and cultural genocide of Indigenous Mexican people in the name of Catholic conversion.

Moreover, there is a sense of movement about the painting, and in the circles there is a long line of ancestors, blurring the line between past and present in time, reminding us of the past’s relevance in the present. Mexican style and color imagery present in these ancestors (through distinctive styles of hats, natural color schemes, and patterns) proclaim Chicano pride and beauty as a form of authenticity and resilience. The audience understands the sentiment that Chicanos are not alone in this fight, as Viva La Raza is written in ribbon outlining the bottom of the painting. This historical protest phrase represents a long history of the Chicano movement. Additionally, the Chicano man’s fists may not only be repeated for emphasis but also to represent the endless solidarity of those with the fight.

Furthering the solidarity of the Mexican ancestors are depictions of Indigenous Mexican people and the Mexican flag combined with United States imagery in the form of the blue, white, and red flag. This may be a potential critique: Indigenous Americans (including Chicanos) are the real Americans, owners of their rightful land, though not accepted as real Americans—while the U.S. is cast as the Chicanos’ oppressor.

This work represents Chicano resilience amongst oppression, pride, and strength in community. As a student, I know the alarming hypocrisies evident in today’s political climate that pay no attention to history. For example, racist mass deportation and the scapegoating of Mexican immigrants as the cause of economic hardship in the United States ignore Chicanos’ native right to their Indigenous land stolen in early colonial periods, in the Mexican-American War, and/or by imperialist America. Mass deportation in 1930s Los Angeles and sportswashing due to city planning for the Olympics plant grave shadows of what we see reflected in today’s mass deportation and upcoming 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

I am consistently reminded that the only reason there is Chicano ethnic studies curriculum, improved school systems in Latino communities, improved farm workers’ rights, etc., is due to endless protests on the account of Chicano people throughout history. These people were often faced with life-threatening violence, and many people died in the midst of each cause. Nothing would have changed if it were not demanded through an organized people.

Today, we commemorate, honor, and learn about Chicano history and art such as The Chicano Mind by Guillermo Martinez in an attempt to both understand and apply this knowledge to present threats to Chicano self-determination.